TL;DR: In a recent camping trip we noticed just how cold our propane tank was getting after cooking for a while - we started out pretty chilly anyway (about 50 F). The physics of this is cool and I wanted to play with modeling it.

I have one of these little two burner propane stoves that we use when camping, it looks something like this:

While we were cooking breakfast and boiling water for coffee, we noticed that the propane tank was getting super cold - there was not only a thick layer of frost forming on the outside, but a small chunk of solid ice on the bottom of the tank where it met the picnic table…

The propane in the tank is stored as a liquid under pressure relative to atmospheric. The pressure in the tank will be the saturation pressure of propane at the temperature of the tank (at any temperature and pressure conditions humans find comfortable). As we use propane, the pressure in the tank tries to drop below the saturation pressure and some of the liquid propane evaporates, bringing it back up. Turning that liquid into a gas absorbs energy from the surroundings - which in this case is the liquid propane itself (and the tank). The liquid cools down (because of that evaporation), which in turn will lower the saturation pressure of the propane in the tank. As the liquid becomes colder than the ambient air, heat will start to flow back into the tank from the surroundings - the bigger the difference in temperature between the tank and the surroundings, the faster the heat will flow to balance the heat lost to evaporation.

A couple of things to see if we can model here:

- Can we model the temperature of the tank for given starting conditions (ambient temperature, initial tank temperature, etc.)?

- Will the temperature drop be significant enough to freeze water that condenses on the tank?

- Will it reach a stable temperature at some point as the heat lost to evaporation is balanced by heat flow back into the tank? What would happen if we insulated the tank?

We’re going to hopefully end up with a simple, directionally correct model - that could be further refined to include more details if we wanted to. Maybe I’ll bring a thermometer, scale, and stopwatch on the next camping trip to get some real data to compare to…

Modeling the set up

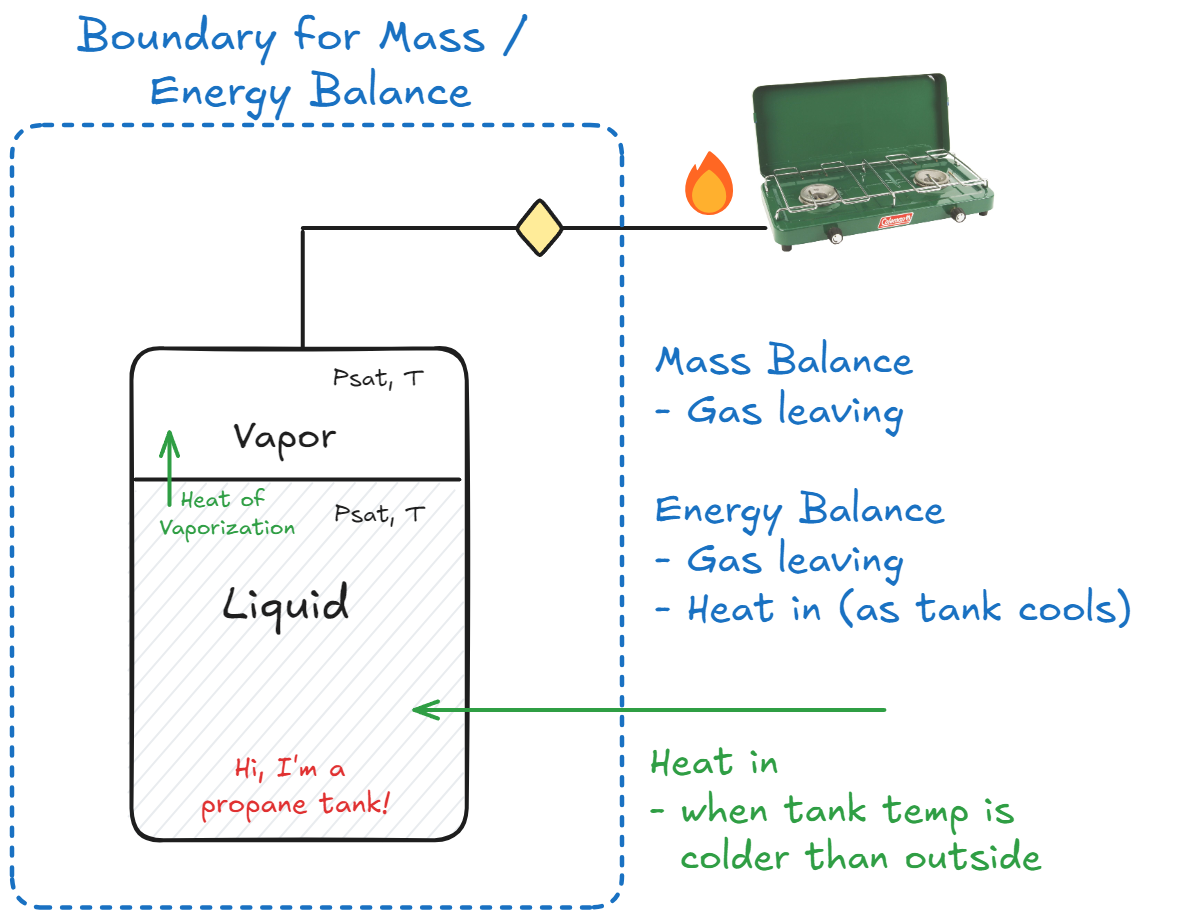

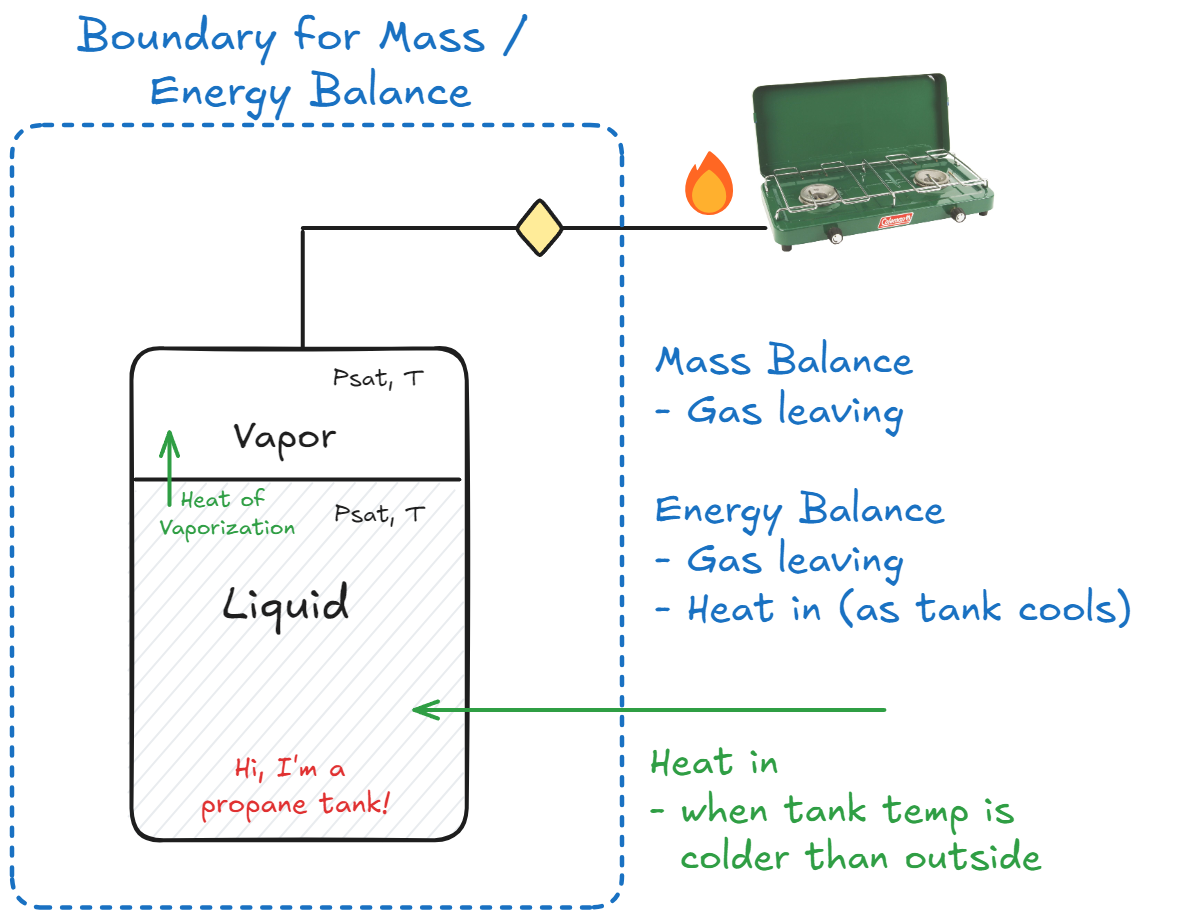

In classic ChE fashion, let’s start with a little diagram of the system, and where the interesting boundaries are:

I think one of the first things to do is to get an idea of the properties of propane

- Are we talking about reasonably low enough pressures that we can get away with using ideal gas law?

- Is it likely even liquid in that tank? (you can hear it sloshing around when you shake it, but let’s check anyway…)

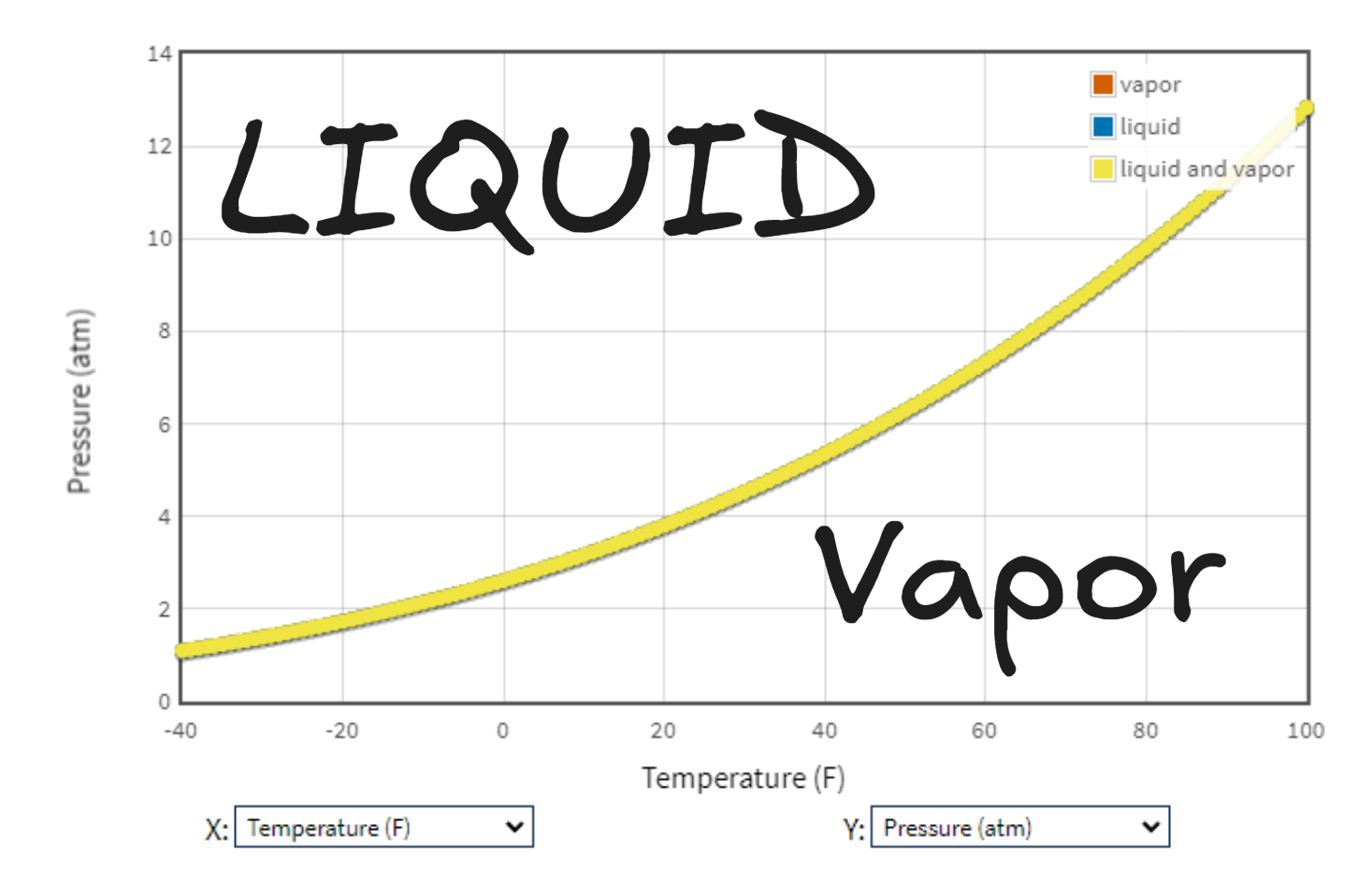

I used NIST’s webbook to get the saturation properties of propane in the temperature range we’re interested in here, this is what the saturation pressure looks like:

This is telling us that at any temperature and pressure above the curve we have a liquid, and below we have a gas. So at our ambient temperature of about 50 F, at pressures above ~6.3 atm (or 93 psi) we have liquid propane. These tanks need to be rated for at least that, or really they need to be OK for the pressure at the highest temperature they might be exposed to (plus some safety factor), which could be much higher than 50 F - say it was 100 F outside - then the pressure would be about 12 atm (or 176 psi). The tank has a warning not to exceed 120 F, which would be about 16.5 atm (or 242 psi). Some sources suggested that the pressure relief valve may release at just over 200 psi, but I didn’t find a consistent reliable source on the pressure limits of the tank. However, all the numbers seem reasonable to me for a 1 lb propane tank.

Based on this info, we can see that we’ll be dealing with propane at between 1 atm (14.7 psi) and 16.5 atm (242 psi) (really at a max of 6.3 atm (93 psi) for our specific ambient temperature of 50F). The ideal gas law is an OK assumption here for the gas phase. It’s required for our simplified mass flow rate estimate. We could either use tables or a better model (a more sophisticated equation of state) to improve accuracy if we wanted to. In our case at 50 F, the compressibility factor is about 0.85 - a measure of how much the gas deviates from ideal behavior - at the highest possible pressure of 16.5 atm (based on the tank warning of not exceeding 120F), the compressibility factor is about 0.74 - so we’re not ideal but not given all the assumptions we have to make in this model, it’s probably good enough to start out with. We can always come back and refine it later!

So we have a tank of propane at some initial temperature, connected to the stove with the valve initially closed. When we open the valve, the propane flows and we start cooking.

Using our little diagram from before:

And the following assumptions:

- The propane in the tank is at a uniform temperature, and starts at the same temperature as the ambient air (50 F) (it was left outside overnight for example)

- The gas phase is reasonably well described by the ideal gas law $ PV = nRT $

- Some properties are temperature and pressure independent in the ranges we’re looking at:

- The heat capacity of the liquid and gas propane (not true but reasonable)

- The heat of vaporization of propane (also not true but reasonable)

- The heat transfer coefficient between the tank and the surroundings - this was pretty difficult to get a good estimate for and the problem is actually pretty sensitive to it. I think actual data would be really useful for refining this estimate

- We’re ignoring heat transfer with the tank itself (it’s thin and the heat transfer coefficient is high)

- Also ignoring the heat transfer with the gas phase propane in the tank (it’s a small amount of mass and lower heat transfer coefficient than liquid)

We can start with a mass and energy balance:

- There’s nothing (no mass) going into the tank

- Whatever mass of propane gas leaves the tank must be equal to the mass of propane that evaporates from the liquid to replace it

- The energy required to evaporate the propane comes from the propane itself and the surroundings

If we can get a good estimate of the mass flow rate of propane out of the tank, we know how much propane is evaporating from the liquid. Given that we know the heat of vaporization of propane, we can calculate the energy required to do this - which will be absorbed from the propane itself and the surroundings. So the $ \dot m_{leaving} = \dot m_{evaporating} $. The change in internal energy of the liquid propane in the tank as a function of time can be described as $ \frac{dU}{dt} = M_{tank} C_p^{l} T $, where $ C_p^l $ is the heat capacity of the liquid propane, and $ M_{tank} $ is the mass of liquid in the tank. The change in internal energy is completely due to (1) the evaporation of the liquid propane and (2) the heat transfer from the surroundings so that we get:

$$ \frac{dU}{dt} = M_{tank}C_p^l\frac{dT}{dt} = \dot m_{evaporating}\Delta H_{vap} - hA_{tank}(T - T_{ambient}) $$

Newton’s Law of Cooling was used to describe the heat transfer between the tank and the surrounding air, so that heat transfer rate is $ hA_{tank}(T - T_{ambient}) $, where $ h $ is the heat transfer coefficient, $ A_{tank} $ is the surface area of the tank, $ T $ is the temperature of the tank, and $ T_{ambient} $ is the temperature of the surroundings.

This gives us a simple differential equation to solve for the temperature of the tank as a function of time, solving for $ dT/dt $:

$$ \frac{dT}{dt} = \frac{\dot m_{evaporating}\Delta H_{vap} - hA_{tank}(T - T_{ambient})}{M_{tank}C_p^l} $$ We can use the initial conditions of the tank to get started and solve it numerically to get an idea of how the temperature of the tank changes with time.

The only thing we’re missing at the moment is an estimate of the mass flow rate of propane out of the tank. We know the pressure drop across the valve - we know the pressure in the tank because we’re at the saturation pressure for our current temperature. We can get it from an Antoine equation, from a table, using an EOS, or using the Clausius-Clapeyron equation to estimate. In this model I grabbed the Antoine equation coefficients for propane from NIST and used those.

So if we know the pressure drop across the valve, we can theoretically solve for the flow through the value. At certain pressure drops the flow will be “choked”, the velocity will be fixed at the speed of sound - and under these conditions (Choked Flow) we can use a simplified estimate of the mass flow rate of propane out of the tank:

$$ \dot m = \frac{\gamma A_{valve} P_{tank}}{\sqrt{\frac{C_pT_{tank}}{MW}}} $$

It could be improved if we know more about the actual valve - but we’re not going to worry about that here (we could use the discharge coefficient, etc. if we wanted to).

For propane, we’re in “choked flow” when the pressure in the tank is about 1.7 times the pressure at the outlet (ambient pressure) - it’s related to the ratio of constant volume and constant pressure heat capacities. Looking at the saturation pressure curve, we expect this to be the case for the majority of the time we’re using the stove until we either run out of liquid propane in the tank or the temperature in the tank drops below about -20 F (where the saturation pressure is about 1.7 atm and we’d have to switch to another approach to estimate the mass flow rate).

Running the model

Let’s run this model for some reasonable conditions to see what we get. We’ll use the initial conditions to get started, and iterate through time to get an idea of how the temperature of the tank evolves:

- Set the initial conditions (ambient temperature, initial tank temperature, etc.)

- Compute pressure in the tank (using the saturation pressure of propane at the current tank temperature)

- Calculate the mass flow rate of propane out of the tank

- Compute the temperature change of the tank, using a linear approximation (Euler method) to approximate a solution to the differential equation: $ T{k+1} = T{k} + \frac{dT}{dt}_k \Delta t $ where $ \Delta t $ is the time step we choose, $ k $ is the index of the time step we’re on and $ \frac{dT}{dt}\vert_k $ is the value of the derivative at time index $ k $.

- Update the mass in the tank $ M_{tank} = M_{tank} - \dot m_{evaporating} \Delta t $

- Go to 2 if we haven’t run out of propane in the tank (or crossed the choked flow limit)

For example, we can do this in Python and plot the results to see how the temperature of the tank changes with time - we also get an idea of how long the propane will last in our tank model!

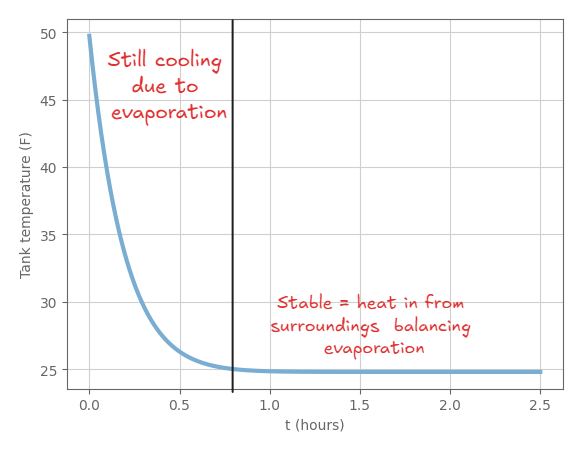

Here’s a plot of the temperature of the tank as a function of time, using some reasonable estimates for the heat transfer coefficient, area of valve, area of the tank, and the fluid properties of propane as indicated above:

This is a simple model - but some cool things we can see:

- It does seem reasonable that the tank would freeze water that condenses on it, given the temperature drop we see in the model

- The temperature of the tank does reach a stable temperature at some point - the heat transfer in from the surroundings (due to the temperature difference) balances the heat lost to evaporation - the temperature where this happens is pretty sensitive to the heat transfer coefficient in air, which was of course one the more difficult things to find a good estimate for

- If we were to insulate the tank very well, the temperature would drop even more quickly, which means the pressure in the tank would drop (see the saturation pressure curve) - this will eventually lead to dropping below the choked flow limit, and the flow will begin to decrease - finally as it cools further the flow will stop completely. I guess this the reason why RV people use propane tank warmers - which is not something I thought about before!

- Ice forming on the tank will increase the surface area of the tank, but it will also insulate the tank, so we’d have to consider the heat transfer properties of ice to get a better estimate of whether it’s increasing or decreasing the exchange of heat with the surroundings. The ice itself freezing from the condensed water will also heat the tank, which is not something we’ve built into this model - but it’s a cool idea to think about. I also expect that because the ice forming on the tank is kind of sparse and frosty, it’s probably got a lot of air trapped between the ice crystals and that might might make it more insulating than just a solid block of ice - but that’s purely speculation on my part. Of course that also means it’s got a lot of surface area to exchange heat with the surroundings, so there are a lot of competing effects there.

- Coleman’s site says the 2 burner stove should last about an hour with both burner’s on high and normal sized camping propane tank, we’re getting about 2.5 hours for 1 burner, which to me suggests we’re surprisingly in the ballpark.

That’s all

This was a fun little exercise, remembering some of the basics of heat and mass transfer and trying to apply them - I used to be a ChemE not too long ago after all! Looking forward to collecting some real data on the next camping trip to compare to this model, maybe even insulating the tank to see how that affects things. Afterward I can refine it a bit more and see how it does compared to the actual data. Might be a while though - it’s getting a little too cold out there for camping in New England.

If you followed along, if you have any questions, notice mistakes, or would have set up the model differently, I’d love to hear about it!