TL;DR - working out the number of draws it will take to get an Ace if pulling cards randomly without replacing them. Just doing it as “an exercise to the reader” - sparked by some questions that came about in an Advent of Code discord server I’m in. I work out the expected number of draws to the first ‘success’ (drawing an Ace from a deck of cards, for example) from first principles, in a not-necessarily-rigorous-but-good-enough way (mathematicians don’t @ me.)

Number of Draws to Success

Problem setup

There are 13 normal playing cards (eg. Ace-2-3….King) of a single suit that have been well shuffled and laid on the table face down. We want to figure out How many draws are needed to draw the ace? (on average)

Using a combinatoric approach

To use the combinatoric approach:

- How many ways can the Ace be in spot $k$ out of 13 cards?

- How many ways can the other 12 cards be arranged in the remaining 12 spots?

Take the case where the Ace is in spot $k$.

- The are 12 other non-Ace cards (2-King).

- To fill the first $k-1$ spots, pick any $k-1$ out of the non-Ace cards. There $12 \choose k-1$ combinations which can be permutated in $(k-1)!$ ways.

- For the $k$ spot, there’s one way to fill it (with the one Ace).

- To fill the remaining spots, there are $13-k \choose 13-k$ (just 1) combination which can be permuted in $(13-k!)$ ways.

Plugging it all in:

$$ t = {12 \choose k-1} \cdot (k-1)! \cdot 1 \cdot {13-k \choose 13-k} \cdot (13-k)! $$ $$ t = \frac{12!}{(k-1)!(12-k+1)!} \cdot (k-1)! \cdot (13-k)! $$ $$ t = \frac{12!}{(13-k)!} \cdot (13-k)! = 12! $$

Where $t$ is the total number of arrangements with the Ace in spot $k$. Another way to look at this, a simpler way for sure - is that the Ace is fixed in spot $k$ - so there are 12 other positions available for the other remaining cards. They can be placed into those places in $12!$ ways - which is a much simpler way to get to the same conclusion.

So given that there are $13!$ ways to arrange the 13 cards overall, the probability of getting $k-1$ non ace cards, and the ace in spot $k$ is $\frac{12!}{13!} = \frac{1}{13}$.

Using this result, the the expected value of the number of draws needed to get the Ace is: $$ E = \sum_{k=1}^{13} k \cdot \frac{1}{13} = \frac{91}{13} = 7 $$ So the number of cards flipped to the first ace will average out to 7 in this example.

The counter-intuitive part

We get that the probability of getting the first ace on any specific draw is equally likely. It feels like you should be more likely to get the ace on the draws near the end. I think that this a (maybe sometimes sub-conscience?) confusion between the probability of drawing $k-1$ non Aces AND drawing the Ace on draw $k$ and the probability of drawing the Ace on draw $k$ GIVEN that you have drawn $k-1$ non Aces, the later conditional probability does change for each draw. In this case, we have drawn $k-1$ cards non Aces already, the Ace needs to be in spot $k$ , so there are $(13-k)!$ different possible arrangements of the rest of the cards. Dividing by the total number of arrangements of $13-(k-1)$ cards $(14-k)!$ - gives: $$ P(Ace_k | NA_{k-1}) = \frac{(13-k)!}{(14-k)!} = \frac{1}{14-k} $$ So given that you are on draw $k$, you do have a higher probability of getting the Ace of course, and it keeps increasing as $k$ goes up until there’s a single card left.

This is also what you get if you run a simple Monte Carlo Simulation in Python to check the results.

Mo’Aces, Mo’Problems

Lets use a full deck and try to apply the same combinatoric approach (there are other some other approaches to get the solution as well). So to restate the problem, we have a well shuffled normal deck of 52 playing cards, and would like to know on average, how many times will we need to draw to get the first Ace. Same as before, but we just have 4 Aces to care about now.

Trying the same thing as before, assume the first Ace is in spot $k$

- There were no Aces in the first $k-1$ cards (or we would have stopped)

- There are now three more Aces mixed in to the rest of the cards

So like before:

- To get the first $k-1$ (non Ace) cards, we have to choose $k-1$ cards from the remaining 48 (total non-Aces) and we can arrange those $k-1$ cards in $k-1$ ways (like before)

- The Ace is in spot $k$ for sure - but we have 4 ways to do this this time, it could be an ace of any suit

- Now the rest of the $52-k$ cards can be arranged in $(52-k)!$ ways

This looks like: $$ t = {48 \choose k-1}\cdot(k-1)!\space\cdot 4 \cdot (52-k)! = \frac{48!}{(48-k+1)!} \cdot 4 \cdot (52-k)! $$ and to get the probability of drawing the first Ace on draw $k$ , the total number of possible orders is:

$$ P(A_k) = \frac{48!}{(48-k+1)!} \cdot 4 \cdot \frac{(52-k)!}{52!} $$ and finally the expected value: $$ E = \sum_{k=1}^{49} k \space\cdot P(A_k) = 10.6 $$ So you will get an Ace on average after about 10 or 11 draws. Here’s some a python snippet to compute it:

import math

def p(k):

# Using the factorial approach

# - computing the actual number of ways that draw

# can be set up so that you draw k-1 non Aces and

# and get an ace on draw k

f = math.factorial

return f(52 - k) * 4 * f(48) / f(48 - k + 1) / f(52)

sum([x * p(x) for x in range(1, 50)]) # 10.599999999999994

But there’s more than one way to approach the problem…

Other approaches

While I was trying to understand different ways of working out this problem, I found a lot of resources and different approaches, some much simpler than others…

My attempt to work it out The way that I approached the problem was only considering Aces and non-Aces. I didn’t really even consider working out the total number of possible combinations as above. This method also works and is simpler to understand in my opinion, but it might just be a me thing. For the problem with 13 cards and 1 Ace:

- If we draw the Ace on turn $k$ - we had to draw non-Aces the $k-1$ turns before

- We had some probability of drawing the Ace on that turn in this case. It’s the number of aces (1 in the first example) out of the number of cards left (we already saw $k-1$ non-Aces)

So for:

- $k=1$ - we have $p(1) = 1/13$ - just the chance of drawing the ace on the first go

- $k=2$ - we had to have missed on draw one, the chances of that are $12/13$ - and then we have to get the Ace here - but we have one less card, so we have a $1/12$ chance to get the Ace and $p(2) = \frac{12}{13}\frac{1}{12} = \frac{1}{13}$

- $k=3$ - we had to have missed on both the first draws. The probability of that is the probability of missing the first ($12/13$), missing the second ($11/12$) , and then getting the Ace - but out of two fewer cards now ($1/11$) - so that $p(3) =\frac{12}{13}\frac{11}{12}\frac{1}{11}=\frac{1}{13}$

- And so on. In this case they all cancel nicely to $1/13$ as we expected, and $E = \frac{1}{13}\sum k = 7$

The same logic applied to the full deck is more tedious (with 4 Aces and 52 total cards):

- $k=1$ - $p(1) =4/52$ - just the chance of pulling the ace on the first go

- $k=2$ - miss the first draw $48/52$ - then get an Ace $4/51$ - (there’s one less card to worry about)

- $k =3$ - miss the first two draws $\frac{48}{52}\cdot\frac{47}{51}$ , and then get an Ace, with 50 cards left $4/50$

- And so on until $k=49$ when there would be nothing but Aces left

There’s an obvious pattern that emerges for each $k$ and it’s:

$$ p(k) = \frac{4}{52-k+1}\space \prod_{i=1}^{k-1}\left(\frac{48-i+1}{52-i+1}\right) $$ If we plug this is into Python, we get the same old $10.6$ result:

def p(k):

# Using the overall probability appoach

# - getting the ace on draw k is the prob that

# you didn't get it on draws k-1, and you got

# it on k

prod = 4 / (52 - k + 1)

for i in range(1, k):

prod *= (48 - i + 1) / (52 - i + 1)

return prod

sum([x * p2(x) for x in range(1, 50)]) # 10.599999999999994

Very intuitive approach This answer on SO presents a very intuitive and less abstract way to think about this problem. The probability that any card, say the 2, shows up before the Ace is $1/2$ . Basically if the cards are laid out randomly it can be either before the Ace or not. This holds for each other card, they all individually have a $1/2$ chance of being before the Ace. Because in this case there are 12 non-Aces, the average number of cards preceding the Ace will be $12 \cdot 1/2=6$ - so there will be six draws on average before the Ace is drawn - we have to add 1 to actually draw the Ace, coming to the same answer of 7. The same line of reasoning works for the full deck too - each of the 48 non-Ace cards has a 1 in 5 chance of being pulled before an Ace is. Then on average the number of cards that precede the Ace will be $48 \cdot 1/5= 9.6$ , and drawing the Ace makes it $10.6$.

A nice shortcut: it’s a math-y way to get there, but I guess problem follows a specific distribution (a negative hypergeometric distribution) - the math to get there is beyond my current probability and statistics skills - but it boils down to an incredibly simple expression for the expected number of draws to the first success: $$ E = \frac{N+1}{k+1} $$ where $N$ is the total number of cards, and $k$ are the number of ‘winning’ or ‘success’ events, that we will stop when we draw. For our two examples so far it’s $E =\frac{13 + 1}{1 + 1} = 7$ for the small case and $E =\frac{52 + 1}{4 + 1} = 10.6$

Monte Carlo Simulation

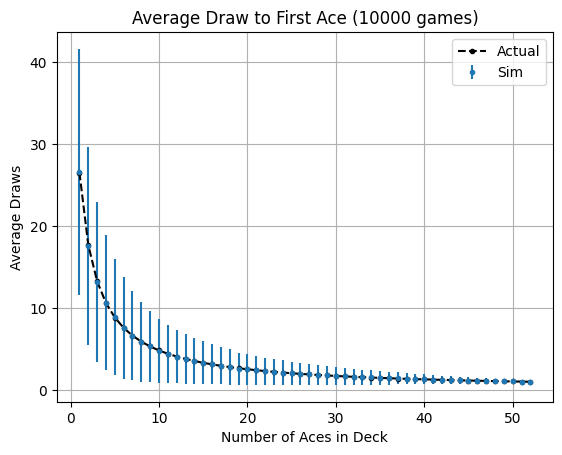

Of course we have to check this all out with a simple simulation - just set it up run and play the “Ace picking” game, keep track of the results, and see what happens. The code to run both the problems is available in this notebook. The simulations agree with our findings above! We can also change the number of Aces or total cards, and re-run and then compare it to the theoretical value, I did that in this notebook (modified version of the previous one). This is what we have:

Thanks for riding along as I reminded myself how to do probability. If you have a different way of approaching the problem, suggestions, or notice any errors, I would be happy hear from you!