TL;DR: re-write the recursive function so that the 1st call doesn’t need to wait for the result from the remaining calls, all the way down to the base case, before returning.

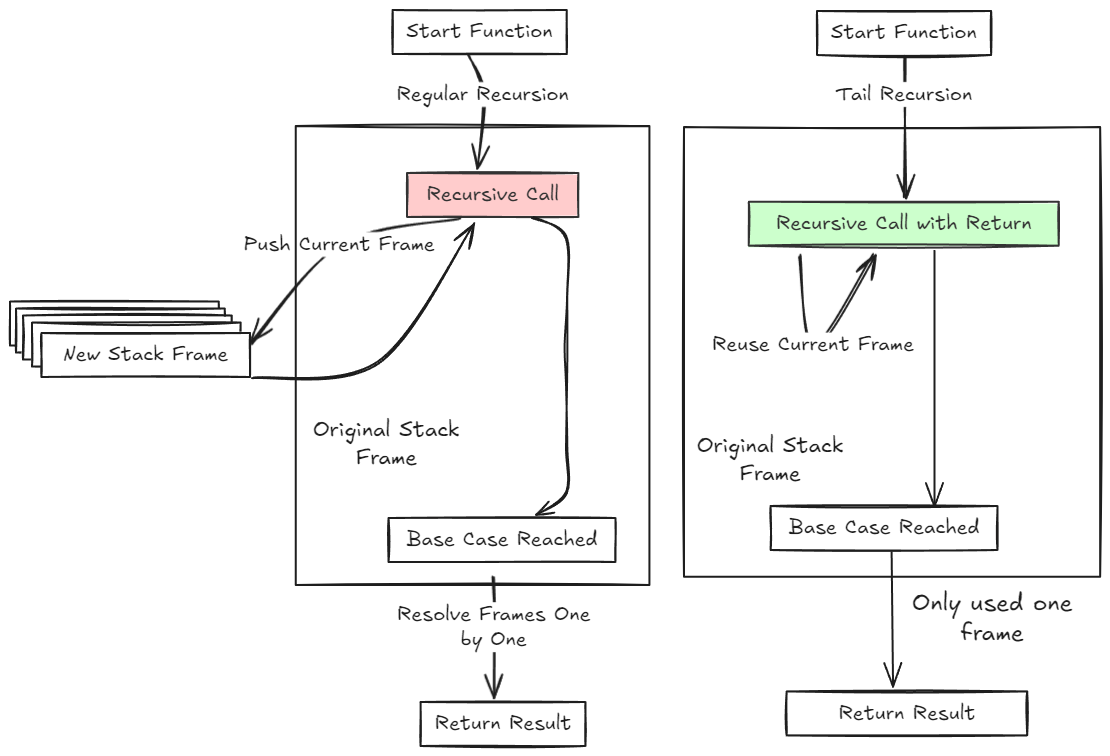

Recursive functions continue calling themselves until the base case is hit - and then they return. The continued calls keep pushing frames onto the stack and can lead to a stack overflow for large inputs. Some languages include an optimization that cleans this up, provided that the function is written in a way that it doesn’t need to wait for the results for all the other recursive calls to resolve to return. See the Tail call optimization wiki for more info (read: a less hand wavy explanation) and a list of languages that support it (and some that explicitly don’t).

Here’s a little diagram that attempts to demonstrate the difference:

I was first exposed to this oddly via typehero.dev - during their Advent of Typescript last year - turns out a lot of witchcraft is possible in Typescript’s type system using recursion (check out some of the later days in the challenge from last year). Now that I’ve started to really look at functional programming, it’s come up again in the Ocaml docs - and to make an effort to understand it fully I threw together some simple examples, a couple are from the docs.

The first is a simple function to get the length of list recursively:

(* Non tail-recursive list len function *)

let rec len lst =

match lst with

| [] -> 0

| _::t -> 1 + len t

In this case the evaluations look like:

(*

# Exploding stack - len [1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6]

# --> 1 + len([2; 3; 4; 5; 6])

# --> 1 + (1 + len([3; 4; 5; 6]))

# --> 1 + (1 + (1 + len([4; 5; 6])))

# --> 1 + (1 + (1 + (1 + len([5; 6]))))

# --> 1 + (1 + (1 + (1 + (1 + len([6])))))

# --> 1 + (1 + (1 + (1 + (1 + (1))))

# --> # --> 1 + (1 + (1 + (1 + 2)))

# --> 1 + (1 + (1 + 3))

# --> 1 + (1 + 4)

# --> 1 + 5

# --> 6

*)

The first evaluation hangs out and has to wait for the results from the rest until it finally returns, so that the first stack frame needs to hang around and it can’t be cleaned up - the same for each subsequent call until it hits the base case.

Versus the tail recursive version:

(* Tail recursive len function *)

let len_tr lst =

let rec len_tr' lst current_len =

match lst with

| [] -> current_len

| _::t -> len_tr' t (current_len + 1)

in

len_tr' lst 0

The stack for this one looks like:

(*

# Constant stack size - len [1; 2; 3; 4; 5]

# --> len([2; 3; 4; 5; 6], 1)

# --> len([3; 4; 5; 6], 2)

# --> len([4; 5; 6], 3)

# --> len([5; 6], 4)

# --> len([6], 5)

# --> len([], 6)

# --> 6

*)

Each evaluation can return, it doesn’t have the value hanging out waiting like the first version does, and if the language supports it, the same frame is reused.

Here’s a few other examples:

Sum of a list:

(* Non tail-recursive sum function*)

let rec sum lst =

match lst with

| [] -> 0

| h::t -> h + sum t

(* Tail-recursive sum function *)

let sum_tr lst =

let rec sum_tr' lst current_sum =

match lst with

| [] -> current_sum

| h::t -> sum_tr' t (current_sum + h)

in

sum_tr' lst 0

Factorial:

(* Non tail-recursive factorial function *)

let rec factorial n =

match n with

| 0 -> 1

| _ -> n * factorial (n - 1)

(* Tail-recursive factorial function *)

let factorial_tr n =

let rec factorial_tr' n current_factorial =

match n with

| 0 -> current_factorial

| _ -> factorial_tr' (n - 1) (n * current_factorial)

in

factorial_tr' n 1

Fibonacci:

(* Non tail-recursive fibonacci function *)

let rec fibonacci n =

match n with

| 0 -> 0

| 1 -> 1

| _ -> fibonacci (n - 1) + fibonacci (n - 2)

(* Tail-recursive fibonacci function *)

let fibonacci_tr n =

let rec fibonacci_tr' n a b =

match n with

| 0 -> a

| _ -> fibonacci_tr' (n-1) b (a+b)

in

fibonacci_tr' n 0 1

Of course these are all trivial examples, but definitely helped me to understand it better. If you’re working on this, I think it was good exercise to start with a normal function and then make it tail recursive (if possible).

I dropped all these examples in a Gist if you want to run them or see more context.

I also did these in Python - even though it doesn’t matter in Python because there’s no tail call optimization in the interpreter. You can see those in the Gist as well. It seems like the argument against adding is that it makes debugging stack traces harder, and maybe they it’s not quite ‘pythonic’.